Mobile money is touted as a promising new way to “bank the unbanked” and as a “product for the poor” for the three-quarters of the world’s population who lack access to a formal bank account. Yet there’s more to mobile money than the practicalities of service delivery.

Like any product, mobile money has aesthetic dimensions that are built into the product design, and that are experienced by the product’s users. What designers envisage, and how people actually interact with a product aesthetically, are not always the same thing.

Mobile phone aesthetic practices are not limited to customization, branding, or even mobile infrastructure. Rather, phones are part of an aesthetic ecology through which repertoires of practices and meanings emerge. Understanding mobile phone aesthetics can therefore be as much of an exercise in analysing kinship relations or communications practices as it is about form, design, and style.

Mobile money is a particularly interesting aesthetic case because it appears to involve making cash disappear from view into the ‘virtual’ world of banks. How can we understand the aesthetics of this transformation from a tangible object (cash) into digital form?

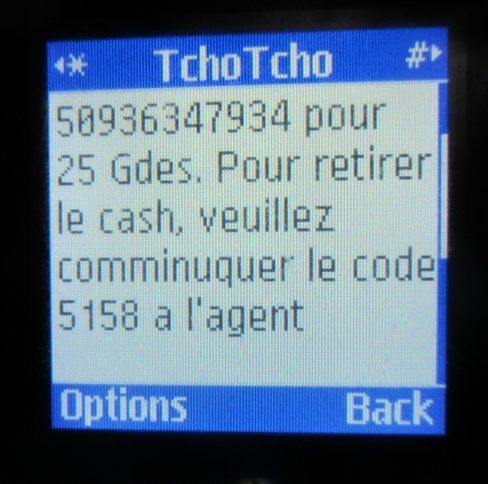

Heather Horst and I explore the aesthetic dimensions of mobile money in a chapter in The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media (2014). Drawing upon research carried out in Haiti in 2010 and 2011, we examine the design, aesthetics and use of Digicel’s TchoTcho Mobile and Voila’s T-Cash. Here I summarize our findings on two aspects: text and display.

The aesthetics of text

Mobile money allows account holders to store and transfer money using text menus and messages on their mobile phone. Not tied to an actual bank account, it allows people to send small amounts of money at low cost from their own mobile phones.

Between November 2010 and October 2012 there were two very different types of interfaces for mobile money services in Haiti. Digicel opted for a text interface in which customers navigate through lists of choices. Conversely, Voila’s T-Cash used a number-based system that did not require navigating text menus. Instead, T-Cash customers entered a string of numbers to make a transaction, and hit “send.”

Both systems permitted customers to check their balance, transfer money, top up the credit on their phone, and change their PIN numbers. The choice of text messaging versus text menus as the key interface for mobile money services has both aesthetic and functional implications. To be functional, text menus need to be readily navigable and comprehensible, and to have appeal, thought needs to put into their design and style. How these are needs are balanced depends upon the target market.

Within the context of Haiti there are numerous reasons why a practical aesthetics rather than a more elaborate one might come to dominate design decisions. First, most people have ordinary phones (not smartphones), so the mobile money system must be set up for text menus and SMS, not internet access.

Second, Haitians are universally numerically literate but the textual literacy rate is approximately 53 percent. Most Haitians have no problem using a mobile phone to make calls or check their balance. Technically, T-Cash should have been easier to use because it only required the entry of numbers; however, literacy was necessary to be able to read a T-Cash pamphlet to work out which string of numbers to use. Some Haitians adjusted to the text menus by memorizing commands so that they can make transactions without having to read the actual text.

Literacy is not the only linguistic factor affecting customers’ ability to use mobile money. Like many post-colonial countries, there are two official languages in Haiti, Haitian Kreyol and French, and also the increasing encroachment of English in the day-to-day vernacular. Kreyol is spoken by the entire population of roughly twelve million people, and is considered to be the “language of the people,” whereas French is the language of administration and formal business and is spoken or partially spoken by about half the population. TchoTcho Mobile advertises and publishes in Kreyol, but their text menus are all in French.

Language in this context is deployed not so much for practical purposes as it is for branding a product with a particular symbolic meaning, which may then increase its appeal to poorer social sectors. Non-French-speaking customers tend to adapt by memorizing the commands, in a similar way to illiterate customers.

The aesthetics of display

In the early literature on mobile phones, status and display emerged as two of the most important aspects of mobile phone consumption. In contrast to other sites and locations, however, the use of the phone for display is not a core preoccupation in Haiti. In fact, Haitian aesthetic practices often has far more to do with hiding wealth and status. While there are some people who will carry around a Blackberry just to be seen to own the phone, these cases are fairly unusual.

Mobile money fits neatly into this aesthetic. Storing money on a SIM card is essentially a way of making it disappear from view by converting it from cash to electronic form. Unlike Kenya, where remittances became the “killer product” for mobile money, we found that Haitians were making more transactions of a kind we called “Me2Me” – using their mobile money accounts to store money and withdraw later. The most significant motivation for this practice was security concerns. Storing cash on your phone is more secure than hiding money in a pocket in your underwear or in the rafters of your house (both common practices).

Concealment for security and privacy

Some Haitians signed up for mobile money so that they would not have to carry cash around town. For example, we talked with Jean Yves, a restaurant worker, in a cybercafé in downtown Port-au-Prince as he was depositing 100 gourdes (US$2.40) into his TchoTcho Mobile account. His brother Michel, who owns the business, had recommended that he register for this mobile money service so that he would not have to carry money across town and risk being robbed. Taking his brother’s advice, Jean Yves signed up and began to regularly deposit cash on his phone at the cybercafé, withdrawing it from a clothing store in his neighbourhood.

People may also use mobile money to hide their cash from themselves. As one an artist explained, “If I have money in my pocket, I will use it on beer, cigarettes and women, but if it is not there I cannot spend it as fast. After all, money is the devil, it makes you do crazy things.” In this case, the practical logic of storing money by putting it out of reach is the same as storing money in a money box (which must be broken to extract the cash), or using a rotating savings and credit association (ROSCA).

Mobile money transactions are also less visible than bank transactions. Depositing or withdrawing money in a clothing store or a newsagent can be much more private than depositing money in a bank, because a person who sees you enter a mobile money agent cannot know whether you are going to make a mobile money transaction or simply buy something that the shop stocks. Transactions become obfuscated by being mixed up with other activities, a process sometimes known as “security through obscurity.”

Transferring money to others can also be done under much more private conditions as they move the process away from the public sphere and decrease the amount of social intermediaries or gateways that one has to pass through to circulate cash. Moreover, relationships themselves can be played out much less publicly.

Money affirms and solidifies social relationships, and sending money to someone can be a signifier of affection or obligation. Hence mobile money allows people to not just protect their store of value but also their emotional relationships from the public gaze. Again, this brings to mind definitions of aesthetics as being emotional responses to sensory perceptions.

Concealment as a cultural logic

While, at first glance, the practice of concealment appears to be prompted by security concerns, it has significant parallels with a broader–and far older–cultural logic. If we look at the Haitian aesthetic in the wider sense, we find that aesthetic practices in relation to personal possessions are driven by more than pragmatism. In Haiti it is a widely accepted practice to avoid ostentatious or ‘flashy’ displays, whether in the form of technology, money, clothing, or information.

Whereas their Dominican neighbours favour a fashion aesthetic characterized by ‘bling,’ with diamantés and other adornments liberally sprinkled upon jeans, bags, shoes, and mobile phones, Haitian fashion tends to be characterized by colourful yet simple, almost minimalist, designs. The rule also extends to money, which is normally hidden on the person or in a safe place. Many Haitian markets sell money boxes (lidless wooden boxes with a slot through which banknotes and coins is inserted) in an assortment of shapes that are designed to hide the fact that they are stores of cash.

Practice of concealing may be grounded historically in the scarcity of resources and differential power over them, yet they are so widespread that it has become part of a Haitian habitus that extends far beyond concerns for personal security.

Concealing is an important part of aesthetics in art, religion, economic practice, and interpersonal relations. Haitian “naïf” paintings commonly hide the faces of the people they depict, highlighting instead commercial activities in outdoor marketplaces, especially the colourful dresses of the Madame Sara vendor women and the fruits and vegetables they are plying.

The anthropologist Karen McCarthy Brown describes how vodou rituals involve simultaneous practices of concealing and revealing as a way of communicate indirectly. Indeed, directly asking for information may not the best way to acquire it. More than fifty years ago, Sidney Mintz documented negotiating practices among market vendors and customers, noting how skilled the women were in changing both price and quantity to achieve an agreeable solution without making overly strong demands. Timothy Schwartz has noted the difficulties of working with local NGOs, in which information is used to barter for employment.

Even Haitian currency, the gourde, is rarely referred to, though universally distributed, as Haitians prefer to count in the fictitious “Haitian dollar.” Concealing, rather than revealing, dominates communication and consumption across a range of domains.

Aesthetics beyond the object

The aesthetics of any given object cannot be reduced to our perceptions of the object itself. Rather, the aesthetic ecology in which the object exists, our social imaginaries of the material world, and even the political economy in which we are embedded shape our aesthetic judgements.

Aesthetics, according to this understanding, can never be simply an emotional response to a perceived form, but are also shaped by the abstractions of our social imaginaries and the political economies in which we are embedded. They are formed by social and object forms that we cannot directly perceive, except insofar that their social meanings are objectified in things, as much as by the material objects that we detect sensorily.

When approached using this definition, mobile money practices reflect social and cultural logics. As research demonstrates, practices of sharing, missed calls, call me messages and others have multiple effects in the hands of users.

This is also true of mobile money, as many of its uses are not anticipated by mobile money designers or people working in socio-economic development. The source of these multiple effects stems from the fact that even the most prosaic products are incorporated into, and reflective of, the social-cultural logic in which they are embedded.

The research discussed in this article was carried out in Haiti with Heather Horst and Espelencia Baptiste between 2010-2012. It was funded by the Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion (IMTFI) at the University of California, Irvine. You can read the full chapter in the Routledge Companion to Mobile Media and download our other papers from Academia.edu.